More Information

Submitted: December 26, 2025 | Accepted: January 05, 2026 | Published: January 06, 2026

Citation: Dolo SS, Mpofu L. Community-driven Nutrition Interventions in Mali: Effectiveness, Barriers, and Lessons from the Dioila Health District. J Community Med Health Solut. 2026; 7(1): 001-008. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jcmhs.1001064

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jcmhs.1001064

Copyright license: © 2026 Dolo SS, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Community-based nutrition interventions; Nutrition support groups; Implementation science; Social Cognitive Theory (SCT); Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR); Maternal and child nutrition; Women’s empowerment; Behavior change; Qualitative research; Mali

Community-driven Nutrition Interventions in Mali: Effectiveness, Barriers, and Lessons from the Dioila Health District

Sulemana Seidu Dolo1,3* and Limkile Mpofu2,3

and Limkile Mpofu2,3

1Ministry of Health and Social Development, Department of Public Health, Bamako, Mali

2Department of Psychology, College of Human Sciences, University of South Africa (UNISA), 0002, South Africa

3Department of Post Graduate Studies, Health Sciences, Africa Research University (ARU), Zambia

*Corresponding author: Sulemana Seidu Dolo, Ministry of Health and Social Development, Department of Public Health, Bamako, Mali, Email: [email protected]

Background: Malnutrition continues to threaten the health and survival of children and women in sub-Saharan Africa. Mali faces persistent undernutrition despite multiple national initiatives. The Ministry of Health established Nutrition Support Groups (Groupes de Soutien à l’alimentation et à la Nutrition – NSGs) to enhance infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and household nutrition through peer-led, community-based interventions. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), this study explored the effectiveness, barriers, and lessons learned from the operationalization of GSANs in the Dioila Health District, Mali.

Objective: The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness and operationalization of Nutrition Support Groups (NSGs) in improving community nutrition outcomes in the Dioila Health District of Mali. Specifically, the study aimed to explore the perceived effectiveness, enabling factors, barriers, and sustainability mechanisms influencing NSG implementation. Using an integrated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) approach, the study sought to understand how structural determinants and behavioral processes interact to shape nutrition-related practices and community empowerment.

Methods: We employed a descriptive qualitative design between January and June 2024. Six focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with 48 participants (24 mothers, 16 facilitators, and 8 community leaders). Data were transcribed, translated, and thematically analyzed using NVivo 12, guided by CFIR domains and SCT constructs. Trustworthiness was ensured through triangulation, member checking, and reflexivity.

Results: Five main themes emerged: (1) Enhanced awareness and behavioral change; (2) Women’s empowerment and peer learning; (3) Economic and time constraints; (4) Influence of cultural norms on feeding practices; and (5) Sustainability challenges and weak supervision. NSGs increased nutrition awareness and self-efficacy but were limited by insufficient resources, irregular monitoring, and social norms restricting women’s autonomy.

Conclusion: NSGs demonstrate strong potential to improve maternal and child nutrition outcomes through social learning, peer influence, and empowerment. However, sustainability and equity require institutional support, community financing mechanisms, and culturally responsive interventions. Integrating Nutrition Support Groups (NSGs) within district health plans and strengthening supervision will improve long-term outcomes.

Malnutrition remains a major global public health challenge, contributing to an estimated 45% of deaths among children under five years of age worldwide [1]. Despite sustained international efforts, undernutrition continues to disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where it remains a leading cause of childhood morbidity and mortality [2]. Beyond immediate health effects, malnutrition has long-term consequences for physical growth, cognitive development, educational attainment, and economic productivity, reinforcing intergenerational cycles of poverty and poor health [3].

In Mali, child undernutrition persists as a critical public health concern [4]. Evidence from nationally representative surveys and recent secondary analyses indicates a high prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight among children under five, with only modest improvements over successive survey rounds [5]. The burden is especially pronounced in rural districts such as Dioila, where household poverty, seasonal food insecurity, limited dietary diversity, poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions, and constrained access to health services converge to heighten vulnerability among women and young children [6].

Nutrition-related behaviors in Mali are further shaped by sociocultural norms and household power dynamics. Studies from Mali and comparable Sahelian settings highlight how food taboos, gendered roles, and male-dominated decision-making can limit women’s autonomy over food choices, infant feeding practices, and health service utilization [7]. These contextual factors underscore the need for nutrition interventions that address not only knowledge and skills, but also the social and gender norms influencing behavior.

In response, Mali has institutionalized community-based nutrition approaches, including Nutrition Support Groups (Groupes de Soutien à l’Alimentation et à la Nutrition) within its primary health care and community health strategy [8]. Facilitated by trained community volunteers, these groups use participatory peer-learning methods such as cooking demonstrations, group discussions, and household visits to promote optimal breastfeeding, complementary feeding, hygiene, and dietary diversity. Community-driven models of this nature are increasingly recognized for their potential to strengthen caregiver self-efficacy and sustain behavior change when embedded within local health systems [9].

However, peer-reviewed evidence on the effectiveness, contextual influences, and sustainability of Nutrition Support Groups in Mali remains limited, particularly at the district level [10]. To address this gap, the present study applies an integrated framework combining the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) to examine both implementation processes and behavior change mechanisms [11].

This study, therefore, examines the effectiveness, barriers, and lessons learned from Nutrition Support Group implementation in the Dioila Health District, Mali, to generate practical recommendations for strengthening community-driven nutrition interventions in similar low-resource settings and contributing evidence relevant to national and global nutrition goals, including SDGs 2, 3, and 5.

Study design

A qualitative descriptive design was employed to capture rich insights from participants’ lived experiences. The CFIR framework was applied to identify contextual and implementation determinants, while SCT was used to explain behavioral mechanisms that influence nutrition practices.

Theoretical framework

This study was guided by two complementary frameworks: the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT).

Together, these frameworks provide a dual lens for understanding both structural and behavioral determinants of community-based nutrition interventions.

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)

The CFIR offers a comprehensive structure for identifying contextual and organizational factors that influence program implementation and outcomes [12]. It consists of five interrelated domains:

Intervention characteristics: Attributes of the Nutrition Support Group (NSG) approach, including its design, perceived quality, adaptability, and complexity.

Outer setting: Broader community environment, encompassing social norms, resource availability, economic conditions, and external partnerships.

Inner setting: Organizational features such as leadership engagement, communication channels, and the culture of local health systems.

Characteristics of individuals: Personal traits of facilitators and participants, including knowledge, beliefs, motivation, and self-efficacy.

Implementation process: Key stages of program delivery, including planning, engagement, execution, reflection, and evaluation.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

SCT complements the CFIR by emphasizing how individual behavior is influenced by social and environmental contexts [13]. It highlights four central constructs relevant to community-based nutrition interventions:

Observational learning: Learning through observing and imitating role models, such as peer mothers or facilitators.

Self-efficacy: Confidence in one’s ability to perform specific health and nutrition behaviors.

Reinforcement: Positive feedback or rewards that sustain behavior change.

Reciprocal determinism: Continuous interaction between the individual, behavior, and environment, where each influences the other.

Integration of CFIR and SCT

In this study, CFIR provided the structural lens to analyze how organizational, community, and process-related factors affect NSG implementation, while SCT offered a behavioral perspective on how learning, motivation, and reinforcement drive individual and collective change.

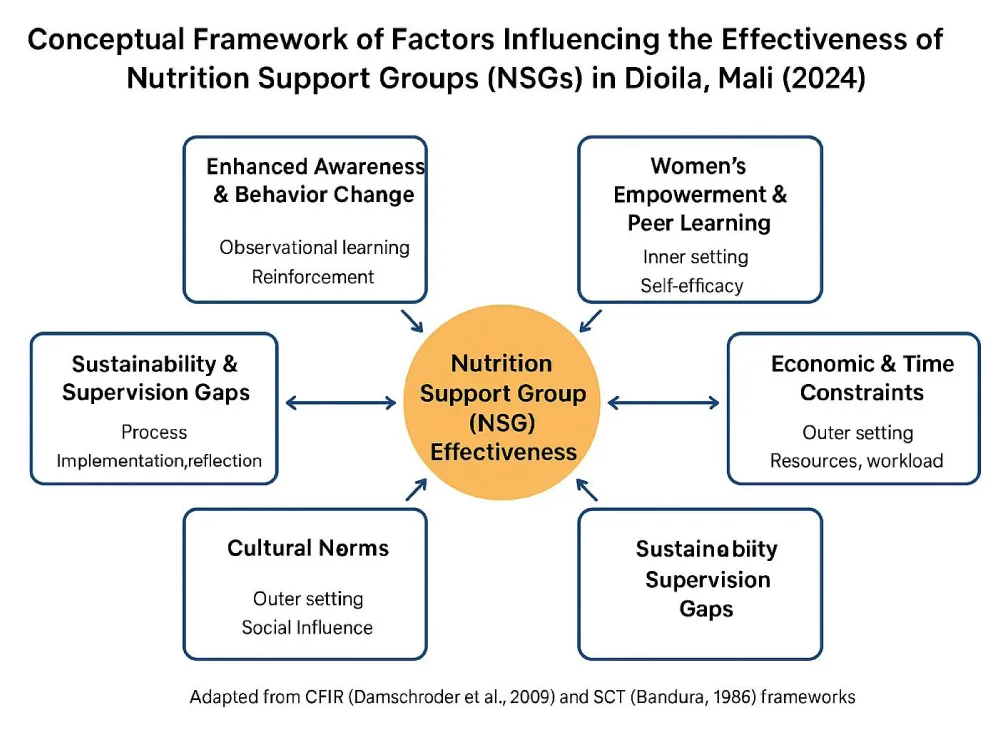

The integration of both frameworks enabled a holistic understanding of how contextual enablers (CFIR domains) interact with personal and social mechanisms (SCT constructs) to influence the adoption and sustainability of nutrition practices in Dioila (Figure 1)[14].

Figure 1: Integrated CFIR–SCT Framework for Nutrition Support Group (NSG) Implementation in Mali.

Study setting

The Dioila Health District, located in the Koulikoro Region, southern Mali, covers 35 health areas and a population of approximately 550,000. Agriculture is the main livelihood, with seasonal migration influencing household dynamics. NSG activities are coordinated through community health centers under the district health management team [15].

Sampling

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to capture a diverse range of perspectives on the functioning and effectiveness of Groupes de Soutien à l’Alimentation et à la Nutrition (NSGs) within the Dioila Health District. This approach was chosen because it allows for the intentional inclusion of individuals who possess rich, context-specific knowledge relevant to the study objectives.

Participants were selected based on their involvement in or interaction with NSG activities, ensuring representation from key stakeholder groups:

NSG members (women of reproductive age, mothers of children under five, and pregnant women), Community health workers (CHWs), Local leaders (including village elders and women’s group coordinators), and Health staff from community health centers.

To ensure variation and data saturation, six communities were selected across Dioila District—representing both urban and rural catchment areas—based on differences in accessibility, population density, and program maturity. Within each community, participants were recruited with support from CHWs using community registers and NSG attendance lists.

A total of six focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted, each comprising 8–12 participants. Sampling continued until thematic saturation was achieved—defined as the point at which no new insights or themes emerged from subsequent FGDs.

Demographic characteristics such as age, marital status, occupation, and participation duration in NSGs were noted to ensure a balanced representation of experiences. This sampling strategy provided a comprehensive understanding of contextual enablers, barriers, and perceived effectiveness of NSGs from multiple community perspectives.

Participant recruitment

Purposive sampling identified participants representing NSG facilitators, mothers, and local leaders. Selection criteria included participation in NSG activities for at least six months. Recruitment continued until data saturation was achieved.

Focus group discussions were conducted separately for mothers, facilitators, and community leaders to encourage open discussion.

Data management and analysis

All audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and subsequently translated into French and English to ensure comprehensive and accurate analysis. Transcripts were systematically reviewed against the original audio files to verify accuracy and completeness before analysis.

Data were managed and analyzed using NVivo version 12 software, following the six-phase thematic analysis approach described by Braun and Clarke. These phases included:

Familiarization: repeated reading of transcripts to achieve an in-depth understanding of the data;

Generating initial codes: systematic identification and labeling of meaningful segments of text;

Searching for themes: grouping related codes into preliminary thematic categories;

Reviewing themes: refining and validating emerging themes in relation to the coded data and the full data set;

Defining and naming themes: clearly articulating the scope, content, and meaning of each theme; and

Producing the report: synthesizing the findings into coherent and analytically robust thematic narratives.

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) domains, intervention characteristics, inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals, and implementation process, and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) constructs, including observational learning, self-efficacy, and reinforcement, served as guiding analytical frameworks.

Coding was conducted using both deductive approaches, informed by these theoretical constructs, and inductive approaches, allowing for the emergence of new themes directly from participant narratives.

To enhance the trustworthiness and rigor of the analysis, several strategies were employed. These included triangulation of participant groups (mothers, community facilitators, and local leaders) to corroborate findings across perspectives; peer debriefing within the research team to refine interpretations and minimize bias; member checking, whereby preliminary themes were shared with selected participants to validate accuracy and resonance; and reflexivity, maintained through analytic memos documenting researcher assumptions, positionality, and contextual influences throughout the analytic process.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Bamako Institutional Review Board and the Malian Ministry of Health and Social Development (Reference No. 2024/UB-IRB/HS-034). All participants provided informed consent before data collection, and participation was entirely voluntary.

To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, unique identification codes were assigned to each transcript, and personal identifiers were removed from all records. Data were stored in password-protected files accessible only to the principal investigators. The study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [16], ensuring respect, beneficence, and justice in all interactions with participants.

Participant characteristics

The study included 48 participants: 24 mothers aged 18–45 years, 16 NSG facilitators, and 8 community leaders (including village chiefs and religious elders). Most participants had limited formal education but substantial experience with community-based activities and local health initiatives.

Overview of emergent themes

Five interrelated qualitative themes emerged from focus group discussions and interviews, reflecting participants’ perceptions of how NSGs function within the sociocultural and economic context of the Dioila Health District (Table 1). These themes illustrate both enabling factors and constraints shaping NSG implementation and perceived outcomes.

| Methods: Key Themes and Illustrative Quotes from FGDs | ||

| Theme | Core Insight | Illustrative Quote |

| Awareness & Practice Change | Improved understanding and application of child feeding and hygiene practices | “I changed how I feed my child; now I add beans and oil.” |

| Women’s Empowerment | Increased confidence and shared decision-making among women | “We decide the meal plan together as women.” |

| Economic & Time Constraints | Poverty and farm workload limit participation and diet diversity | “Work on farms limits us from attending sessions.” |

| Cultural Norms | Traditional beliefs hinder the adoption of recommended foods. | “Grandmothers resist giving meat to young children.” |

| Sustainability Gaps | Weak supervision and limited institutional support | “We need more engagement from health staff.” |

Enhanced awareness and reported behavior change

Participants consistently described improved understanding of infant and young child feeding and hygiene practices. Mothers reported adopting more diverse complementary feeding practices and improved hygiene behaviors, which they attributed to practical demonstrations and peer learning within NSGs. These accounts suggest perceived behavior change driven by shared learning rather than formal instruction.

Women’s empowerment and peer learning

Participation in NSGs was perceived to strengthen women’s confidence and involvement in household nutrition-related decision-making. Facilitators and mothers described peer mentoring and collective discussion as key mechanisms through which women gained confidence to apply new practices. This theme reflects perceived improvements in self-efficacy and social support within women’s networks.

Economic and time constraints

Despite increased awareness and motivation, participants emphasized that poverty, seasonal agricultural labor, and competing household responsibilities limited regular attendance and the ability to implement recommended practices consistently. These constraints were described as external to the NSG model but influential in shaping participation and practice adoption.

Influence of cultural norms on feeding practices

Longstanding cultural beliefs and intergenerational norms were reported to affect food choices for young children, particularly regarding animal-source foods. Participants noted that community dialogue within NSGs helped question and gradually address some misconceptions, although resistance from elders remained a challenge in certain households.

Sustainability challenges and institutional support gaps

Participants identified inconsistent supervision, limited availability of educational materials, and weak integration with district health services as factors affecting NSG continuity. Facilitators and community leaders emphasized that stronger institutional engagement and local resource mobilization were necessary to sustain activities beyond volunteer commitment.

Overall, the qualitative findings indicate that NSGs are perceived as acceptable and valuable platforms for nutrition education and peer support. However, their effectiveness and sustainability are shaped by a dynamic interaction between individual motivation, social norms, economic conditions, and institutional support structures (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Conceptual framework of factors influencing the effectiveness of nutrition support groups in Dioila health district, Mali.

Five interrelated qualitative themes emerged from the analysis, reflecting participants’ perceptions of how GSANs function within the socio-cultural and economic context of the Dioila Health District (Table 1). The themes capture both enabling factors and constraints influencing participation, adoption of recommended practices, and program sustainability. Together, they illustrate the interaction between individual agency, social norms, and structural conditions shaping community-based nutrition interventions.

This study provides qualitative evidence on the perceived effectiveness and implementation dynamics of the Groupes de Soutien à l’Alimentation et à la Nutrition (NSGs) as community-based nutrition interventions in the Dioila Health District, Mali. Drawing on participants’ experiences and perceptions, the findings suggest that NSGs contributed to improved nutrition-related knowledge, peer learning, and women’s confidence in making household nutrition and health decisions. By integrating the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), the study offers a nuanced interpretation of how contextual, organizational, and behavioral factors interact to shape implementation processes and perceived outcomes.

Interpretation through CFIR

From a CFIR perspective, several contextual enablers emerged as central to NSG functionality. Participants perceived NSG activities as culturally appropriate, adaptable, and easy to understand, which enhanced acceptability and engagement. The qualitative data suggest that practical, participatory modalities such as cooking demonstrations and group discussions aligned well with existing norms of collective learning, reinforcing earlier implementation research indicating that adaptability and low complexity support sustained community engagement.

The inner setting, particularly community trust and leadership involvement, was perceived as a critical facilitator. Facilitators who were respected community members enhanced credibility and served as effective intermediaries between health services and households. However, participants also described challenges related to limited supervision, material shortages, and inconsistent logistical support.

These constraints, frequently reported in decentralized health systems, appeared to affect implementation consistency rather than community acceptance.

In the outer setting, socioeconomic conditions and gender norms shaped participation and practice adoption. Women reported difficulties attending sessions during peak agricultural periods and challenges in applying recommended practices due to financial constraints. Gendered decision-making dynamics were also perceived as limiting women’s autonomy over food choices. These qualitative insights highlight the importance of embedding gender-sensitive and livelihood-oriented approaches within community nutrition programs.

Interpretation through SCT

SCT helped explain how behavior change was perceived to occur within NSGs. Participants described learning new practices primarily through observation of peers and facilitators, suggesting that social modeling and reinforcement played key roles. Increased confidence in applying new skills described by participants as “feeling capable” despite limited resources reflects perceived gains in self-efficacy, a core SCT construct. However, respondents also emphasized that motivation alone was insufficient when structural barriers such as food availability and sociocultural taboos persisted. This reinforces the SCT principle of reciprocal determinism, whereby behavior change depends on the interaction between individual agency and enabling environments.

Contribution to existing literature

The findings align with qualitative and mixed-methods studies from West and East Africa showing that community-based, peer-led nutrition interventions can foster positive changes in knowledge, norms, and self-efficacy, while facing sustainability challenges related to financing and institutional support [17]. Consistent with prior research, this study suggests that community empowerment mechanisms are necessary but not sufficient; long-term effectiveness depends on integration with health systems and broader socioeconomic interventions.

Policy and practice implications

Several implications emerge from this qualitative analysis. First, formal integration of NSGs into national and district health and nutrition strategies could enhance sustainability through clearer accountability and resource allocation.

Second, strengthening facilitator supervision, training, and motivation may improve implementation fidelity.

Third, linking NSGs with economic empowerment initiatives such as savings groups or home gardening could help address financial barriers that limit practice adoption. Finally, engaging men and community leaders appears essential for addressing gender norms that influence household nutrition decisions.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is the application of an integrated CFIR–SCT framework, which enabled a comprehensive qualitative interpretation of both implementation processes and perceived behavior change mechanisms. However, the findings are based on self-reported experiences from a single district and should be interpreted as context-specific. The qualitative design does not permit causal inference or quantification of nutritional impact, and reported changes reflect participants’ perceptions rather than measured outcomes. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable implementation-focused insights to inform program adaptation and future mixed-methods research.

This study demonstrates that the Groupes de Soutien à l’Alimentation et à la Nutrition (GSAN) constitute an effective, community-driven mechanism for improving maternal and child nutrition in Mali. Through peer education, participatory learning, and women’s collective action, NSGs have successfully enhanced nutrition knowledge, promoted positive feeding behaviors, and strengthened women’s confidence and decision-making capacity. These outcomes confirm that locally owned and socially grounded interventions can generate meaningful and sustained improvements in community health.

The integration of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) provided a multidimensional understanding of NSG implementation. SCT illuminated the behavioral mechanisms such as observational learning, self-efficacy, and reinforcement that underpin lasting behavior change, while CFIR revealed how organizational and contextual factors shape implementation fidelity and sustainability [18]. Together, these frameworks offer a replicable model for designing, scaling, and evaluating community-based nutrition programs in other districts of Mali and similar low-resource settings.

To sustain and amplify the impact of NSGs, several actions are essential. First, NSGs should be institutionalized within national and district health planning and budgeting systems, ensuring consistent funding, technical supervision, and policy alignment. Second, capacity building and mentorship for facilitators and community leaders should be continuous, enabling them to maintain motivation and quality delivery. Third, context-sensitive strategies, including economic empowerment activities, male engagement, and intergenerational dialogue, are required to address social and cultural barriers to behavioral change. Finally, strengthening monitoring, evaluation, and learning systems will help track progress, promote accountability, and foster adaptive management of community programs.

In conclusion, NSGs exemplify a scalable and culturally responsive approach to advancing nutrition and gender equity in Mali. Embedding behavioral science within structured implementation frameworks enhances the potential for sustained community ownership and policy integration. As Mali strives to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), and SDG 5 (Gender Equality), NSGs offer a practical, evidence-based pathway for accelerating progress toward improved nutrition outcomes and resilient communities.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, several actionable recommendations are proposed to enhance the sustainability, scalability, and impact of Groupes de Soutien à l’Alimentation et à la Nutrition (NSGs) and similar community-based nutrition programs:

Institutionalize NSGs within national and district health systems. The NSG model should be formally embedded in the Plan Décennal de Développement Sanitaire et Social (PDDSS) and district health plans to ensure consistent funding, technical support, and accountability for community-level nutrition activities.

Strengthen supervision, monitoring, and feedback mechanisms. Regular follow-up by health professionals and community health workers should be institutionalized. Use of digital monitoring tools and community scorecards could improve data accuracy and responsiveness to emerging challenges.

Enhance facilitator capacity and motivation. Continuous training, refresher sessions, and modest incentive schemes (e.g., recognition awards, stipends) can improve facilitator performance and retention.

Integrate economic empowerment with nutrition education. Linking NSG activities with income-generating initiatives—such as home gardening, savings groups, and microfinance—would help reduce financial barriers to implementing recommended dietary practices.

Promote gender-transformative and culturally sensitive strategies. Engage men, grandmothers, and local leaders through community dialogues to address gender norms and cultural beliefs that limit women’s decision-making power and adoption of optimal feeding behaviors.

Foster cross-sectoral collaboration. Nutrition outcomes depend on partnerships across health, agriculture, education, and social protection sectors. Collaborative planning at the district level will ensure coherent implementation and resource sharing.

Support operational research and scale-up evaluation. Future studies should evaluate the long-term impact of NSGs on child nutrition outcomes and household food security, using mixed-methods designs to inform national scale-up strategies.

What is already known on this topic?

Community-driven nutrition interventions, including community health worker–led and group-based approaches, are widely used in Mali to prevent, detect, and manage child undernutrition at the community level.

These interventions contribute to improved nutrition knowledge, early identification of acute malnutrition, and strengthened links between communities and primary health services.

The effectiveness and sustainability of community-based nutrition initiatives are influenced by health system capacity, availability of resources, community engagement, and sociocultural factors.

What this study adds

Provides district-level empirical evidence on the real-world effectiveness of community-driven nutrition interventions in rural Mali.

While national policies promote community-based nutrition approaches, this study offers context-specific evidence from the Dioila Health District, showing how these interventions function in practice, including their contributions to early detection of malnutrition, community engagement, and linkage with health facilities.

Identifies operational and socio-cultural barriers affecting the sustainability and performance of community nutrition initiatives.

The study highlights practical challenges such as irregular supervision, volunteer motivation constraints, limited material support, and gender-related decision-making dynamics—that are often under-reported in existing literature but critically influence intervention outcomes.

Generates actionable lessons for strengthening community-led nutrition programming in similar settings.

By documenting local experiences, coping strategies, and stakeholder perspectives, the study provides program-relevant lessons to inform policymakers, NGOs, and district health teams on how to improve ownership, supervision, and integration of community nutrition structures within the health system.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: SSD and LM; Data Curation: SSD; Formal Analysis: SSD and LM; Investigation: SSD and LM; Methodology: SSD and LM; Project Administration: SSD and LM; Resources: SSD and LM; Validation: SSD

Visualization: SSD; Writing: Original Draft: SSD and LM; Writing: Review and Editing: SSD and LM; upervision: LM

All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript and agree to its publication.

We sincerely thank the Regional Health Directorate and the Dioila District Health Office for their valuable collaboration and logistical support throughout this study. We extend our deepest appreciation to the community health workers whose dedication and commitment were central to the successful implementation of this research.

We are profoundly grateful to the families and community members who participated and generously shared their time, experiences, and perspectives—they remain the true heart of this study. Our gratitude also goes to the local interpreters and data collectors, whose professionalism, cultural sensitivity, and persistence ensured data quality and the integrity of the research process.

Finally, we acknowledge the broader support of colleagues at the Ministère de la Santé et de l’Hygiène Publique, Mali, and the Department of Human Sciences at Africa Research University (ARU), Zambia, for their technical guidance and encouragement.

Consent for publication: Not applicable. This study does not include any identifiable individual data.

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study before data collection. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured of confidentiality and the right to withdraw at any stage without consequence.

Institutional review board statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision) [19] and was reviewed and approved by two institutional review boards:

The Africa Research University (ARU) Research and Ethics Committee, Lusaka, Zambia (Protocol No. HSHDC/0208/2024, approval date 2 August 2024).

The Ministère de la Santé et de l’Hygiène Publique (MSHP) – Ethical Review Board, Bamako, Mali (Protocol No. MOH/ERB/2024/03/09, approval date 3 September 2024).

- When it Matters Most | UNICEF [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/documents/when-it-matters-most

- Lukwa AT, Okova D, Bodzo P, Maseko SC, Bhebe M, Akinsolu FT, et al. Temporal socio-economic inequalities in the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) among under-five Children: An analysis of within- and between-group disparities in 20 sub-Saharan African countries (2004–2024). Glob Transit. 2025 Jan 1;7:262–75.

- Amoadu M, Abraham SA, Adams AK, Akoto-Buabeng W, Obeng P, Hagan JE. Risk Factors of Malnutrition among In-School Children and Adolescents in Developing Countries: A Scoping Review. Children. 2024 Apr 15;11(4):476. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040476

- Malnutrition Is Still a Major Contributor to Child Deaths, but Cost-Effective Interventions Can Reduce Global Impacts | Request PDF. ResearchGate [Internet]. 2025 Aug 5 [cited 2026 Jan 4]; Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242531380_Malnutrition_Is_Still_a_Major_Contributor_to_Child_Deaths_But_Cost-Effective_Interventions_Can_Reduce_Global_Impacts

- Poda GG, Traore F, Traore IFB, Dao F, Poda P. Breaking the Growth Barrier: Uncovering the Prevalence and Drivers of Stunting in Children under Five in Bamako: Briser le Plafond de Croissance : Une Enquête sur la Prévalence et les Facteurs Associés au Retard Staturopondéral chez les Enfants de Moins de 5 Ans à Bamako. Health Res Afr [Internet]. 2025 June 29 [cited 2026 Jan 4];3(7). Available from: https://hsd-fmsb.org/index.php/hra/article/view/6793

- Islam B, Ibrahim TI, Wang T, Wu M, Qin J. Current trends in household food insecurity, dietary diversity, and stunting among children under five in Asia: a systematic review. J Glob Health. 15:04049. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.15.04049

- Advancing women’s roles in nutrition-sensitive agricultural practices in Africa. In: Advances in Food Security and Sustainability [Internet]. Elsevier; 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 4]. p. 203–59. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/bookseries/abs/pii/S2452263525000011

- Re-Established Nutrition Support Groups in Mali Reduce Malnutrition and Increase Access to Health Care - URC [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.urc-chs.com/news/re-established-nutrition-support-groups-in-mali-reduce-malnutrition-and-increase-access-to-health-care/

- Community-based models of care facilitating the recovery of people living with persistent and complex mental health needs: a systematic review and narrative synthesis - PMC [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 4]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10539575/

- Lieven H, Loty D, D D Ampa, Talla F, Moctar O, Francisco B, et al. Reducing child wasting through integrated prevention and treatment in Mali. Intl Food Policy Res Inst; 2025. 8 p. Available from: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a47b632f-1f82-4363-a737-ae0dcba06b43/content

- A scoping review of applications of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to telehealth service implementation initiatives | BMC Health Services Research [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 4]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12913-022-08871-w

- A framework for identifying implementation factors across contexts : Le Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) | CCNMO [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 2]. Available from: https://www.nccmt.ca/fr/referentiels-de-connaissances/interrogez-le-registre/210

- McDowell, I. Theoretical Models of Health Behavior. In: McDowell I, editor. Understanding Health Determinants: Explanatory Theories for Social Epidemiology [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 4]. p. 253–306. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28986-6_6

- Albert Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-cognitive-theory.html

- Sustainsahel - Area 4: Koulikoro [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.sustainsahel.net/study-sites/mali/area-4-koulikoro.html

- WMA - The World Medical Association-WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/

- (PDF) Barriers and Facilitators to the Implementation of Large-Scale Nutrition Interventions in Africa: A Scoping Review [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349640072_Barriers_and_Facilitators_to_the_Implementation_of_Large-Scale_Nutrition_Interventions_in_Africa_A_Scoping_Review

- (PDF) Applying the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to Optimize Implementation Strategies for the Friendship Bench Psychological Intervention in Zimbabwe. ResearchGate [Internet]. 2025 Aug 8 [cited 2025 Nov 1]; Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373163345_Applying_the_Consolidated_Framework_for_Implementation_Research_to_Optimize_Implementation_Strategies_for_the_Friendship_Bench_Psychological_Intervention_in_Zimbabwe

- The Declaration of Helsinki in bioethics literature since the last revision in 2013 - Ehni - 2024 - Bioethics - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 4]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bioe.13270